Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens: A model learning environment.

A National Park service site famous for lotuses and lilies is worth a visit any time of year.

Dear Reader,

My recent posts have promoted my soon-to-be-published book, Learning Environment: Inspirational Actions, Approaches, and Stories from the Science Classroom

However, a recent visit to a local park (dare I say a National hidden gem of one) detailed below is an example and beautiful complement to what you will find within my book’s contents. I hope you enjoy this post (and consider visiting the park).

Note: the most recent version of this post has been edited to include updated information about the DC Nature Near Schools program

Arrival at the Gardens

On a brisk near-spring morning with clear bluebird skies and full sun, I dropped my family off at school and trekked across DC to the Kenilworth Park & Aquatic Gardens. I was invited by Sheena Foster, Executive Director of the ‘Friends of’ group affiliated with this National Park Service site dedicated to water-phillic plants, to observe the outdoor field experience component of a MWEE (pronounced ‘me we’) or Meaningful Watershed Educational Experience of 4th graders from a local DC public elementary school.

Having never been to the gardens before, I arrived early and sat for a few moments in the empty parking lot before Jeff Chandler, the ‘GreenKids’ Director from the local non-profit Nature Forward, pulled into a nearby spot. Greeting Jeff, who I had met the previous week on a pre-trip logistics call, we excitedly chatted about the day ahead and reflected on our shared connection to Hamilton College (I happened to notice our alma mater’s vinyl cling stuck to his car’s back windshield) as we left our cars behind and entered the park.

Making our way into the gardens, I noticed a series of excavated ponds, lying dormant after a cold winter, waiting expectantly for a new crop of water lilies and lotuses they would soon hold. The ponds, whose arrangement and proximity somewhat resembled rice paddy fields, had a series of linking trails that were interspersed with needle-less bald cypress trees (this conifer is one of only a few that shed their modified leaves each winter, hence their ‘bald’ nomenclature) as well as a variety of others. In the distance, at the back edge of the ponds, we could view some of the last remaining natural sections of the Annacostia River’s marshland, whose water’s vital role to the gardens flora and very existence will be revealed below.

After a brief check-in at the Visitor Center, where we connected with the lead Ranger from the National Park service whose colleague would provide students with a history of the Gardens during our station rotations, we regrouped outside. By then, Nature Forward’s other educators, who would engage students in a joyful macroinvertebrate study and water quality analysis, had arrived along with Christy Brock, Director of Programming at the Urban Adventure Squad (UAS), another D.C.-based environment education non-profit on site for a habitat themed nature walk and scavenger hunt around the ponds and marsh.

In case you’re wondering whether or not it is usual for four separate organizations (Friends of Kenilworth, National Park Service, Nature Forward, UAS) to come together on one site for one field trip for one school, let me tell you as a former teacher that it is not. The existence of this collaboration, thanks to funding from DC’s Department of Energy and Environment (DOEE) ‘Nature Near Schools’ initiative, will allow upwards of 1200 4th graders at 29 Title I schools to participate in a MWEE this school year. This unique funding initiative has brought Nature Forward and UAS (as well as three other environmental-ed DC non-profits) together in a brilliantly synergistic fashion. No doubt, the Nature Near Schools granting framework should not only continue but also seems ripe for replication and one that I, my colleagues, and environmental-ed non-profits could have only dreamt about when planning outdoor excursions in and around New York City.

With our crew of educators now fully arrived, along with Friends of Kenilworth’s Program and Outreach Manager, Alivia Villari, we reviewed the day's logistics, including student groups cycling through three stations led by Nature Forward, UAS, and Parks. My role, and one I was rarely privy to as a teacher, was to be a detached yet interested observer - tagging along with one of the three groups so that I could get a feel and provide feedback for the overall trip experience.

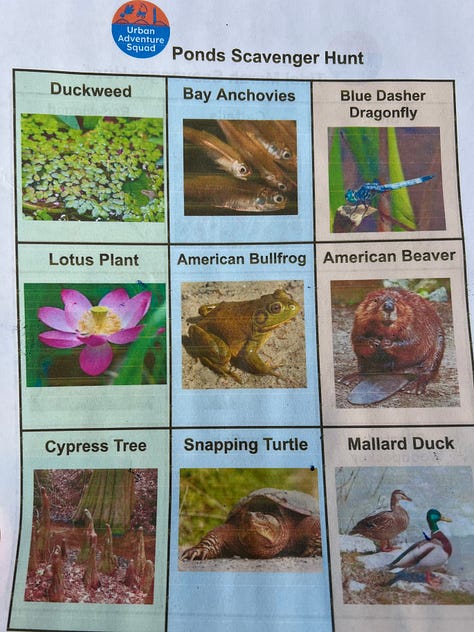

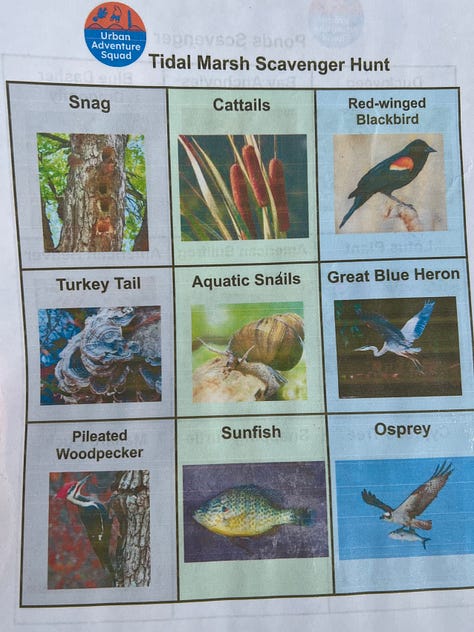

Station 1: Habitat Hike - Urban Adventure Squad

After an excited arrival and subsequent division of fourth graders into three groups, I left the Visitor Center behind with one of them. We set off with Christy of UAS for a habitat hike and scavenger hunt. At the beginning of our walk, Christy had the kids refresh their memories about the four components of habitat (food, water, space, and shelter). We then traversed along the Garden’s pools, seeing multiple pairs of mallard ducks and observable signs of beaver activity on the “knees” or above-ground roots of cypress trees, before turning onto an elevated boardwalk that brought us out, above, and into a tidal marsh.

From our perch above the marsh, we discussed the interconnectedness of local and global waterways. Christy, leaning into the big picture idea that there is, in truth, only one water system, connected the water from the Anacostia River that flows into the tidal marsh (and Gardens) to the water that flows downstream to the Potomac River, Chesapeake Bay, and Atlantic Ocean. During her talk, Christy pointed out the pollutants (some natural, most human-made) floating at the top of the water and how marshland, once thought of as little more than mosquito habitat, actually provides an essential pollution absorption ecosystem service.

Station 2: The History of Kenilworth - National Park Service

Circling our National Park Service ranger in front of one of the smaller ponds in the park, our group learned that Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens, a National Park site since the 1930s, was initially started as a family business enterprise in the late 19th century. In an engaging retelling of the site's history, our ranger informed us that Civil War veteran Walter B. Shaw, who lost his right arm during battle, dug the pond we were standing near with his remaining arm to pursue his passion for growing water lilies. Eventually, thanks to the business acumen and boldness of his daughter Helen Fowler, his hobby grew into a renowned aquatic plant company whose water lily and lotus flowers were shipped around the United States.

While the water plant business, shall we say, bloomed, so did the population of the D.C. metro area, fueling demand for land near the city center and threatening the very existence of the marshland on which the gardens depended for their water. Our group, standing now at the distant marshland side of the gardens, learned from the ranger how Helen knew that without easy access to the water from the Annacostia River, brought to her literal doorstep thanks to its tidal ebb and flow, the ponds (and her business) would dry up.

This reality led Helen to pursue the legal protection of the marsh, which, thanks to public and political pressure (and lots of perseverance over a nineteen-year battle), saw the Federal government reverse its decision to take the marsh via eminent domain and sell it to the Gardens for $50,000 in 1938. From that point forward, Helen lived on the Garden’s property, caring for and training the next generation of water plant lovers, until she died in 1957. (Note - some historical information is cited from the placard image below)

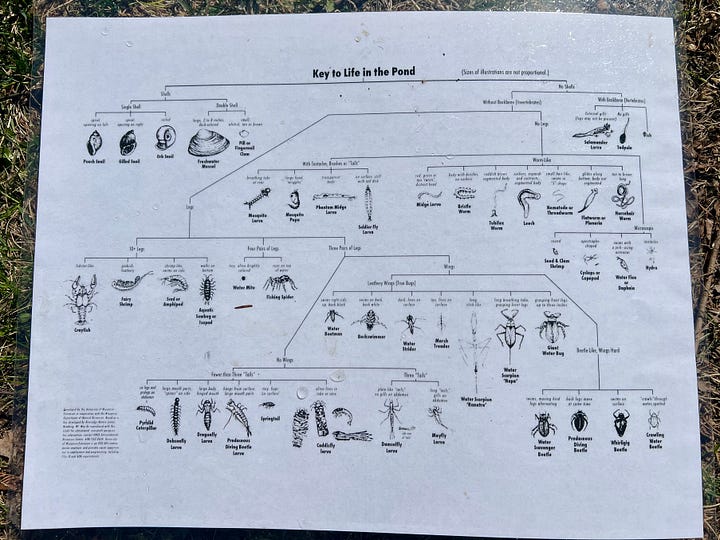

Station 3: Macroinvertebrate Study - Nature Forward

The final station stop for my group, near the peeling bark of a tree precariously perched on the edge of a pond across from the Visitor Center, was Nature Forward’s macroinvertebrate study. Following a brief educator talk, students excitedly huddled around the series of collection bins containing an array of already collected insect larvae and other spineless creatures, including the colloquially named and depending on who you ask “ghost,” “grass,” or “popcorn” shrimp. The entire experience was scientifically and exuberantly playful, which reminded me of my time doing a similar activity at the Ashokan Center in the Catskill mountains, where the presence (or absence) of particular species of macroinvertebrates served as indicators of water quality.

Final Stop and Reflections

Students, having departed back to their school (and the soon-to-be-implemented next step of their MWEE learning sequence—student-informed action projects—think stormwater drain labeling, birdhouse building, and litter cleanups), our nature near schools conglomerate debriefed the day.

Across the board, the team thought the student group and the entire collaboration were great, especially given that this was the first time the Gardens had been used for a MWEE field experience. I, too, a former teacher who has incredibly high standards for what a field trip (or ideally fieldwork) experience should look and feel like for students, was impressed. Undoubtedly, the beautiful weather helped (as did the idyllic natural setting of the Gardens). However, make no mistake, this incredibly well-executed and coordinated interdisciplinary experiential learning experience that students were provided is a model for what learning outside of the classroom can and should be.

As always, thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this post, I highly encourage you to visit the Gardens, especially during the water lily and lotus bloom season (in summer); however, if you’re looking for a more subdued and peaceful interaction with nature, a visit during the off-season should undoubtedly be considered.

Additionally, for those looking to learn more about life in the marsh and be thoroughly engrossed in a story, I cannot recommend enough the book Where the Crawdads Sing (now also a movie) by zoologist Delia Owens. This beautifully written page-turner (that I picked up from a Little Free Library on a recent hike) is part coming-of-age story/part mystery/and part natural history lesson that follows Kya, AKA “Marsh Girl,” through the trials, traumas, and tribulations of raising herself in coastal North Carolina during the 1950s and 60s. While reading, I was taken on a heartwrenching journey through the natural world and wonders of the marsh and reminded of the pressing need for our society to do better for the most vulnerable - both human and wild.

Finally, please remember that your support of my work allows me to make posts like this. Please consider pre-ordering my book, becoming a paid or free subscriber, liking, commenting, or sharing this Substack.

With Gratitude,

Jared